GUIDE: Loadlines

This is a subject which occupies many thousand pages of academic and professional books. However, to the layman there are a few general principles that it is useful to know.

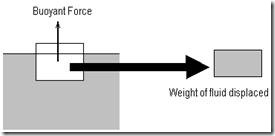

1. Water provides a ‘buoyant force’ against objects placed in it.

Essentially it forces them upwards. The amount of buoyant force pushing upwards is equal to the amount of water displaced by the object. The more water you push out of the way, the more force pushes back against you.

2. A ship floats when the amount of water displaced by its hull weighs more than the ship itself.

So if a ship weights five tonnes but its shape means that its hull is making a hole in the water equivelent to about seven tonnes of water, then it will float. There is a ´buoyant force´ of seven tonnes pushing the object up and only a weight of five tonnes pushing it down.

3. If you load more cargo on a ship it will sit lower in the water.

This seems obvious but what is happening is that the ship becomes heavier than the water it is displacing, and so starts to sink. However, in doing so the hull goes deeper into the water, displacing more water, and eventually the water displaced again becomes heavier than the ship, so the ship stabilises at a floating level again.

4. Ships sit higher in cold or salty water.

This is a major reason why internationally trading ships have loadlines on their sides. The lines correspond to different climates, fresh and salt water, so you can keep at a safe level throughout transit. Salty water is heavier than fresh water and cold water is heavier than hot water. So a ship´s hull needs to displace less, i.e. sit lower, to float. For example, if a ship sits high in the water at Felixstowe (cold, seawater), the same ship dropped into an African lake (warm, freshwater), would sit a lot lower in the water.

Generally, yes, but in the UK, no.

The Athens Convention 1974 applies to the “international carriage” of passengers by sea. It provides for a two year time limit for bringing claims against the carrier (reduced from 3 years under English law generally).

The Athens Convention was brought into law in the United Kingdom by the Merchant Shipping Act 1979. This applied the terms of Athens Convention to all passengers on international voyages, departing from or bound for the UK.

However, in 1987 the UK government the ‘Domestic Carriage Order’[1] was brought into force, which extended the Athens Convention cover to all passengers on voyages which begin and end within the UK, Channel Islands or Isle of Man.

——————————————————————————–

[1] The Carriage of Passengers and their Luggage by Sea (Domestic Carriage) Order 1987

For ten years the Shipping Law Blog has aimed to provide a simple, down-to-earth guide to the world of international shipping and maritime law.

If you have any questions or suggestions please get in touch at editor@theshippinglawblog.com .

Transporting specialized cargo, particularly sensitive items such as human remains, is a delicate task that requires precision, care, and strict adherence to legal and ethical guidelines. Whether the remains are

You often hear reference to oil rigs and platforms, and sometimes people will say, that wasn’t a platform, it was a rig; or the opposite. So why do the terms

The UK Standard Conditions for Towage and Other Services (UKSTC) is probably the world’s most popular towage agreement. The 1986 version is the latest one and probably the most popular.

Most maritime countries in the world apply a two year time bar to collision claims (by virtue of some form of ratification to the Brussels Collision Conventions 1910). In other

Learning to sail is one of the best ways to familiarise yourself with the basics of operating a vessel on water. Many of the terms draw across to the shipping

We often receive queries from readers at the Shipping Law Blog, and today we received one from a non-lawyer, who had been asked to confirm whether one of their contracts

1. All content reserved copyright of theshippinglawblog.com 2015, unless stated otherwise. 2. Header image credit: Paul Gorbould, ‘Leader on Ice’ (Flickr). 3. This website is not intended to provide legal advice and is for interest only. The author does not guarantee the accuracy of any content and, as always, recommends that appropriate professional legal advice is sought by anyone requiring assistance with a shipping law problem. 4. If you have any ideas, recommendations or other queries in relation to the blog please e-mail me at webmaster@theshippinglawblog.com.